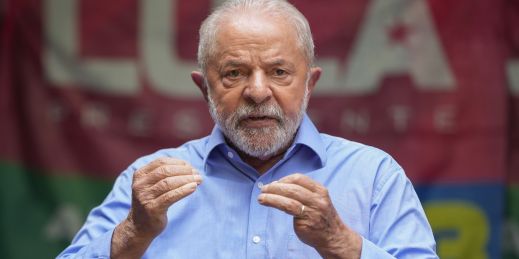

Given the threat that Jair Bolsonaro represented to the democracy of Latin America’s largest country, the whole region should feel some relief that Lula da Silva defeated him in Brazil’s presidential election. And yet, there are many pro-democracy activists in Latin America for whom Lula returning to office is a cause for anxiety.