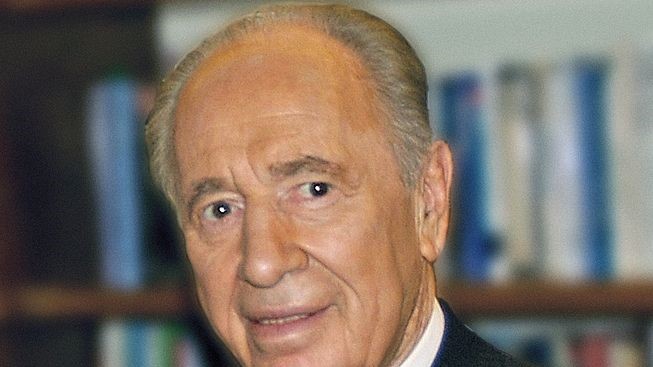

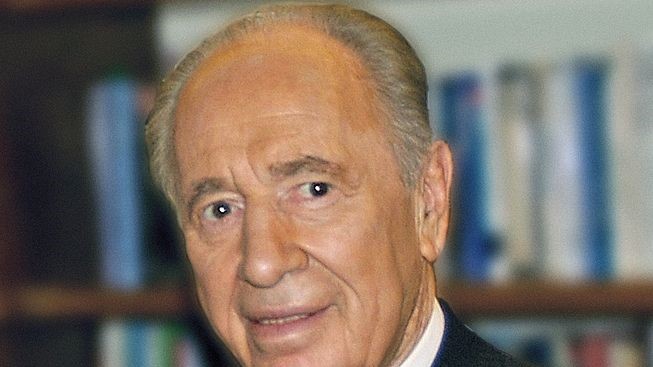

JERUSALEM—The job comes with some nice perks and mostly symbolic duties, but the position, president of Israel, carries enormous prestige, potentially a great deal of influence and, ultimately, a guaranteed spot in the history books.

The race to replace Shimon Peres as head of state is getting off to a star-studded start. The latest candidate to throw his hat in the ring received the Nobel Prize in chemistry a couple of years ago.

But polls show Israelis would like Peres, also a Nobel Prize winner, to stay on for another term.

Already the collection of possible candidates looks like a menagerie of overachievers.

The 90-year-old Peres says he has no interest in a second seven-year stint in the President’s Residence in Jerusalem. Since taking office in 2007, Peres has carried out his duties with surprising vigor and effectiveness, but the law currently does not allow for re-election. The Knesset, Israel’s parliament,

would have to amend the country’s Basic Law to allow him to remain in office.

Presidential elections in Israel are a complicated affair. Candidates require nomination by at least 10 members of parliament. The choice is then made through a secret ballot by members of the Knesset, where Israel’s highly fractious political system is forced to come together to reach a majority vote.

That process introduces a key element in the alchemy that makes it possible to fulfill the presidency’s most important function: becoming a unifying symbol of the state.

The system is designed to prevent transitory political fashions from exerting too much influence in the selection. The winner is meant to stay above politics, signing all laws, receiving diplomatic accreditations from foreign envoys and representing the country at a variety of functions. But the great presidents have also wielded moral power, articulating a vision and ideals for the country. Peres, who in younger years was a practicing politician, with all the unsavory traits that often entails, has performed those above-politics functions exceptionally well.

Voters don’t play a direct role in the election, so campaigning is usually subtle, with efforts to influence legislators and their constituents through different routes.

For the first time, social media may play an important role in this election.

It was, in fact, the scientist who injected a new dose of technology into the system. Last Friday, Daniel Shechtman, a professor of material sciences at Israel’s Technion Institute, the country’s version of MIT, launched his campaign during an interview on Channel 1. Shechtman

won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2011 for the discovery of quasicrystals. A few hours after his announcement, the website Atzuma, Israel’s version of Change.org, posted an online petition to nominate the professor for the presidency, seeking to obtain the necessary backing in the Knesset.

A couple of days later, Shechtman gave another television interview on Channel 10 with more details about his agenda. He explained he had been encouraged by a number of Israelis to make the move, saying he would like to use his problem-solving abilities to help the country. Unlike previous presidents and other candidates, Shechtman has no known political affiliation.

Shechtman is a virtual youngster compared to Peres. His 73rd birthday is this Friday. He says he would like to focus the presidency away from international diplomacy and other politically charged issues, and

focus instead on nurturing a country of people who care about each other, fostering education, technology and enlightenment.

Shortly after that second appearance, the petition passed 10,000 signatures, and the numbers keep rising.

Presumably, campaigning directly before the voters will influence the decision of Knesset members. The competition, however, is steep.

Many names are being considered, including larger-than-life personalities such as the former Soviet dissident Natan (Anatoly) Sharansky. The former chess prodigy and mathematician spent 13 years in the Soviet gulag after becoming a human rights and democracy activist. He became a worldwide symbol of the struggle for human rights and was freed in a dramatic Cold War moment, walking across the Glienicke Bridge into West Berlin and immediately moving to Israel, where he became a leading politician.

Sharansky still maintains the icon status that would serve him well in a quest for the post and in the position, should he win.

Another interesting candidate is former Knesset Speaker Dalia Itzik, who would be Israel’s first elected woman president. Itzik, who retired from politics in late 2012, already served as acting president twice in 2007 when former President Ephraim Katsav ran into legal troubles, first when he took a leave of absence and later when he resigned.

Then there’s retired Brig. Gen. Avigdor Kahalani, an Israeli war hero and one of the country’s most decorated military men. He

played a pivotal role in the 1973 Yom Kippur War, leading a small force of 40 Israeli tanks that held back a Syrian force powered by 500 tanks in a battle eventually won by Israel at a high cost. He received the Medal of Valor, Israel’s highest military medal. After leaving the military he was elected to the Knesset, where he served for several years.

The slate of candidates also includes Yechiel Eckstein, a rabbi, founder of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews and a dual Israeli and U.S. citizen with a distinguished resume and a remarkable track record of philanthropy in addition to his strides in forging relations between different communities.

A number of more conventional politicians are also among the hopefuls. That includes Silvan Shalom, a member of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud Party and the current minister of energy and water. Shalom just attended a conference in Abu Dhabi, a remarkable event because Israeli officials almost never travel in an official capacity to Arab countries with which Israel has no diplomatic relations. And there’s Benjamin Ben Eliezer from the Labor Party, an Iraqi-born former military man and defense minister.

At the moment, the polls show that Israelis’ second choice, just behind the unlikely possibility that Peres will serve another term,

is the well-liked Reuven Rivlin, also from Likud, who served two terms as speaker of the Knesset.

The formal vote is still five months away, and new names are sure to surface. Just as certain is the political maneuvering that is already kicking into gear behind the scene, in one of the most unusual political races in the world, featuring some of the most interesting candidates of any national election.

Frida Ghitis is an independent commentator on world affairs and a World Politics Review contributing editor. Her weekly WPR column, World Citizen, appears every Thursday.