Last week, representatives of signatory states and numerous observer nations, as well as activists from around the world, gathered in New York for the second Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which was negotiated in 2018 and came into force in 2021. In addition to the diplomats at the gathering, scientists and members of communities affected by nuclear testing also took the floor to document the health and humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons. They called for improved norms against the use of nuclear weapons as well as a widened ban on their possession, transfer and stockpiling.

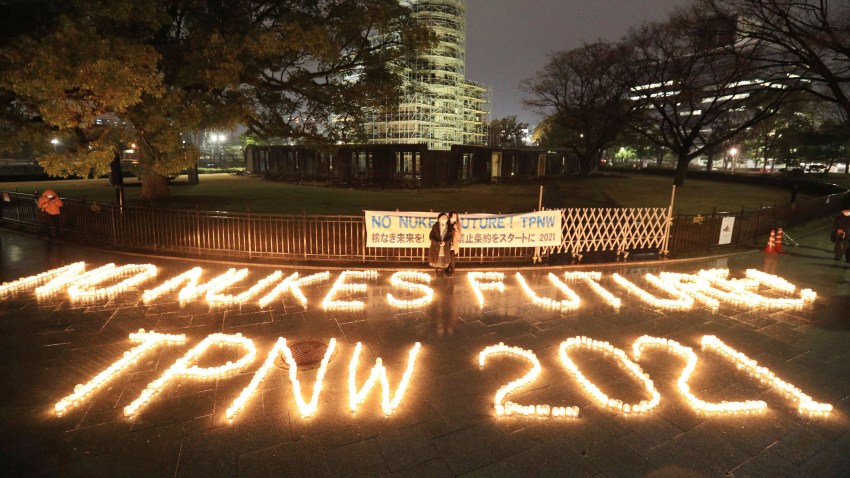

Nuclear-armed states avoided the conference, just as they have avoided signing the treaty or providing requested restitution to affected communities, all of which was called out by civil society observers at the conference. But for many activists and signatory states, this kind of resistance was always to be expected, and immediate participation by the nuclear states was never a necessary condition of the treaty’s success. Rather, campaigners are building a movement that strengthens the stigma against nuclear weapons. The hope is that eventually genuine disarmament might be realized, but also that even if states retain nuclear arsenals, the political space to ever deploy them will shrink, even as awareness of the humanitarian costs of nuclear stockpiling, testing and proliferation grows.

Still, some observers and analysts have wondered whether the nuclear taboo is instead actually weakening under the pressures of resurgent nuclear brinksmanship and nuclear threats as well as unyielding nuclear postures, all of which seem to have coincided with the nuclear ban campaign and treaty. Even Nina Tannenwald, a noted scholar of the nuclear taboo, has questioned whether that taboo is “vanishing.” After all, none of the nuclear powers have signed the ban treaty. Russia, which has repeatedly hinted that the use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine is on the table, pulled out of the nuclear test ban treaty earlier this month. And an Israeli government minister even suggested that Israel could drop a nuclear bomb on Gaza in retaliation for Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack.