The ebb and flow of the Libyan civil war has led most American and European commentators to draw two conclusions. First, the conflict will end with a negotiated settlement. Second, international peacekeepers may be required to make any deal work.

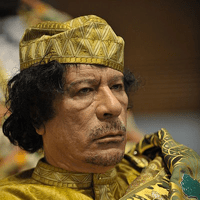

The case for a negotiated settlement is based on the simple fact that a military solution to the crisis is unlikely: The rebels probably cannot win on the battlefield, and Col. Moammar Gadhafi cannot be allowed to do so. A stalemate is also unappealing, not least because it would require the U.S. and Europeans to continue policing Libya's airspace, at significant expense, for the foreseeable future.

So even the most ardent members of the anti-Gadhafi coalition now accept the need to talk to his regime. Three weeks ago, in an article for World Politics Review, I argued that such an effort might involve both covert contacts and overt, U.N.-led diplomacy supported by a "contact group" of concerned countries. Both approaches are now underway.