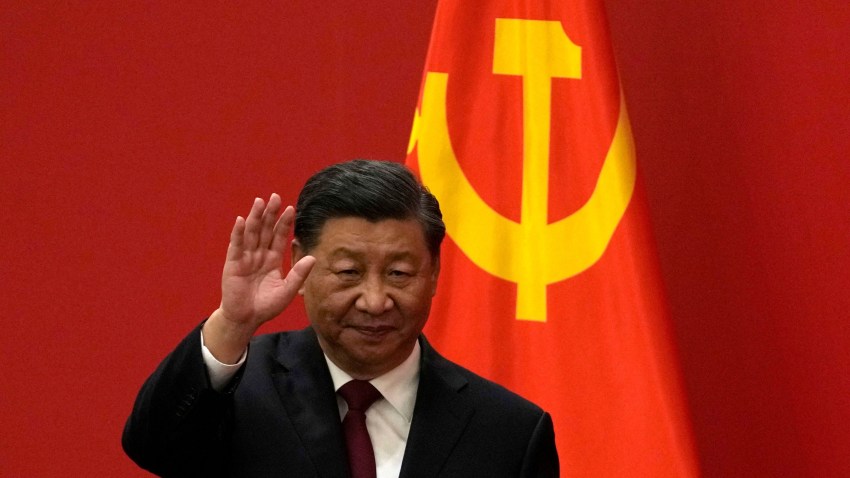

Chinese President Xi Jinping emerged from the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Party Congress last month with his position more secure. He obtained a norm-defying third term as general secretary of the CCP and installed six loyalists to fill out the Politburo Standing Committee, the CCP’s highest policymaking body. Yet, in his speech to the party congress, Xi warned that China faces “high winds, strong waves and stormy seas.” That assessment reflects the many ways in which the country’s strategic outlook is less auspicious than it was before U.S. President Joe Biden took office in 2021.

Indeed, China’s challenges at home and abroad have grown more pronounced in recent years—so much so that a longstanding debate over China’s intentions increasingly coexists with one over its trajectory: Is it on a path to global preeminence, or is it near the zenith of its comprehensive power and perhaps even on the verge of systemic decline?

Between the end of the Cold War and the 2008 global financial crisis, observers tended to underestimate China’s competitive potential on the grounds that it would be difficult for a one-party authoritarian regime to sustain robust growth and maintain popular support. In the 2010s, however, as the CCP demonstrated that it could, in fact, do both, more observers began to conclude that China was on course to emerge as a peer competitor to the United States and potentially even surpass it to become the foremost global power. Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, however, discussions of China’s difficulties have gained renewed prominence, centering mainly around the emerging obstacles to its economic development and the growing pushback from advanced industrial democracies against its trade practices and foreign policy. The outbreak of rare protests this week against the government’s draconian “zero COVID” pandemic response now adds the question of popular discontent to the mix.