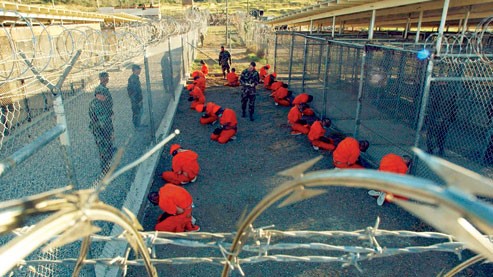

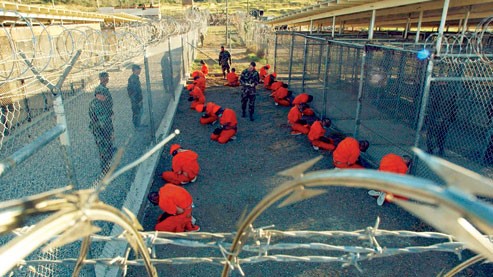

Advocates working to end a sad chapter in American history were given new hope last year when President Barack Obama

renewed his push to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay. The substantive challenges to closing the prison remain, though events have shifted the risk calculus to favor closure. And even though the president is in a far weaker position politically than he was when he took office, different public attitudes on national security issues should make it easier to close Guantanamo. What seemed a hopeless and nearly forgotten project for Obama a year ago—closing Guantanamo by the end of his administration—now seems achievable.

After the latest transfer of one detainee to Algeria last month, 154 detainees remain at Guantanamo. There are three different groups of prisoners among the 154: 76 have been designated for transfer to either their native countries or third countries; 33 are slated for prosecution in either the Guantanamo military commissions or U.S. federal courts; and 45 are to be held in continued U.S. military detention but not charged in any forum.

Congress’ imposition of severe limitations and prohibitions on transferring Guantanamo detainees out of the prison meant that only a handful left between mid-2010 and late last year. But the last few months of 2013 proved to be a turning point. The Obama administration refocused on Guantanamo, and the president appointed senior officials in the State and Defense Departments to oversee the closing of the prison. The momentum carried over into Congress, which voted to lift the most severe restrictions on transferring Guantanamo detainees overseas—the first time it had ever voted to make it easier to close the prison. The revitalized effort has seen more detainees leave Guantanamo in the four months since December 2013 than in the preceding four years combined. The terrain has changed.

When Obama first attempted to close Guantanamo, national security was an extremely powerful political issue. But more than five years later, the war in Afghanistan is winding down, and Osama bin Laden is dead. The American people have grown weary of the constant state of military conflict, and hard national security messages simply do not resonate as they once did. Just last month, when Suleiman Abu Ghaith, a top al-Qaida official and bin Laden’s son-in-law, was convicted in a New York City federal court, hardly anyone noticed—a far cry from the months of debate around the Obama administration’s efforts, ultimately abandoned, to try self-proclaimed 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in federal court.

There remain substantive challenges beyond politics to closing Guantanamo, but even those are not as daunting as they once were, and genuine options are emerging for some of the thorniest problems.

More than half of the Guantanamo detainees are Yemenis, who remain in large number partly because it has been practically impossible to transfer them back to their home country. But a new government in Yemen is demonstrating a greater willingness and capability to tackle its indigenous extremist problem. And a United Nations-led effort to put in place a rehabilitation program for extremists is nearing completion. It is feasible that the program could accept at least the 55 Yemenis already slated for transfer, which would dramatically reduce the Guantanamo population in one move.

The coming end of the war in Afghanistan creates another opportunity to significantly reduce the Guantanamo population. As former Pentagon General Counsel and current Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson observed in 2013, “In general, the military’s authority to detain ends with the cessation of active hostilities.” Seventeen Afghans are still at Guantanamo, and only one of those detainees is a high-level al-Qaida terrorist. There have already been discussions regarding sending five Taliban officials held at Guantanamo back to Afghanistan in a prisoner exchange. Those talks could easily be expanded to include most of the remaining Afghans at Guantanamo.

Prosecuting Guantanamo detainees has proved even more difficult than repatriating prisoners—only four such cases have been concluded in either federal courts or military commissions since 2009. Congress continues to block progress in prosecuting Guantanamo detainees by banning transfers to the United States for trial. The federal courts have successfully handled literally hundreds of terrorism cases since Sept. 11, 2001, while the total number of convictions in the military commissions under the Bush and Obama administrations amounts to seven. But Congress did reverse course on the overseas transfer ban, and the apathy that greeted the Abu Ghaith trial only adds to the likelihood that Congress will also drop the U.S. transfer ban.

Many point to the 45 detainees that even the Obama administration intends to keep in U.S. custody in continued military detention as evidence that the prison will never close. But a closer look at those detainees reveals that this is not as big a problem as it appears. Thirty-six of the 45 are either Yemenis or Afghans. If the same solution could be used for this group of detainees as was found for those in the transfer category, most of the problem would go away. This is not implausible, as a review panel has already determined that one of the Yemenis in this group should have his case re-examined for possible transfer. The U.N. rehabilitation center could make that easier, and several of the Afghans in the proposed prisoner exchange would also come from this group of detainees.

That obviously would not resolve the entire problem, but it would reduce the number of detainees in the category of those deemed too dangerous to release down to just nine. The risk calculus is significantly different when contemplating the potential release of just a handful of detainees rather than the dozens first identified by the Obama administration. It would take courage to simply release them, but closing Guantanamo was never going to be easy.

Guantanamo can be closed. The prison is very expensive and wasteful. Osama bin Laden is dead, and the war in Afghanistan is ending. The American people have grown weary of constant political fighting over national security. It’s time Washington moved on too.

Ken Gude is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. His recent papers include "Guantanamo: America's $5 Billion Folly" and "What Has to Happen to Close Guantanamo This Year."

Photo: Guantanamo captives, Jan. 2002 (U.S. Navy photo by Petty Officer 1st class Shane T. McCoy).