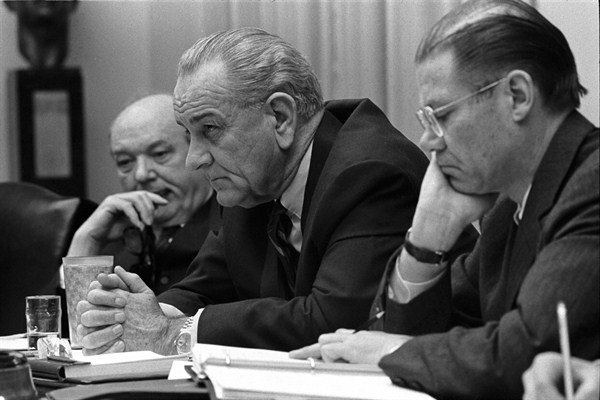

In the fall of 1967, when then-President Lyndon Johnson looked out from his increasingly isolated perch at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, the signs of discontent and anger about the war in Vietnam were increasingly evident.

A majority of the country negatively viewed his handling of the war, and for the first time since the U.S. intervention in Vietnam had begun, Gallup found that a majority of Americans believed the war was a mistake. On Johnson’s political left, anger over the war had reached a boiling point. In October, 100,000 anti-war demonstrators marched on the Pentagon in the largest anti-war protest in American history. On Capitol Hill, congressional support for the war was eroding, as both anti-war liberals and more-moderate Republican hawks began to raise greater concerns about Johnson’s strategy in Vietnam and his lack of candor on the war’s progress. The once supportive news media joined in as well, with the New York Times calling the war a stalemate and Time noting that the “only audible consensus” in the country was the one building against the war. Finally, Johnson began to hear from his own staff. In November, then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara told the president in no uncertain terms that he did not believe it would still be possible for the U.S. “to accomplish [its] objectives” in Vietnam.

Faced with this growing opposition, Johnson faced a crucial decision point: either quickly ramp up the war effort in order to try and win it, or begin U.S. disengagement from the conflict. Instead, Johnson chose door No. 3: to continue the same flawed middle-ground policy of insufficient escalation that he’d been following since U.S. combat operations in Vietnam began in 1965.