The sheer magnitude of the elections taking place in India make them historic and worthy of international attention. But even if the contest had more familiar proportions it would still constitute a major event in world affairs. The choice of India’s next leader

is sending nervous chills down some people’s spines.

The next government in New Delhi will have the power to shake up the world’s largest democracy, the globe’s second-most-populous country and a nuclear-armed nation with a history of ethnic strife and a sense of unfulfilled economic potential.

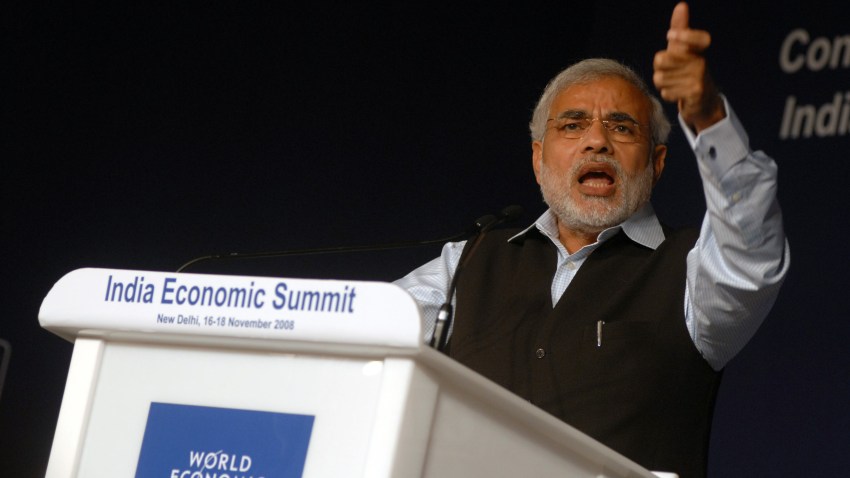

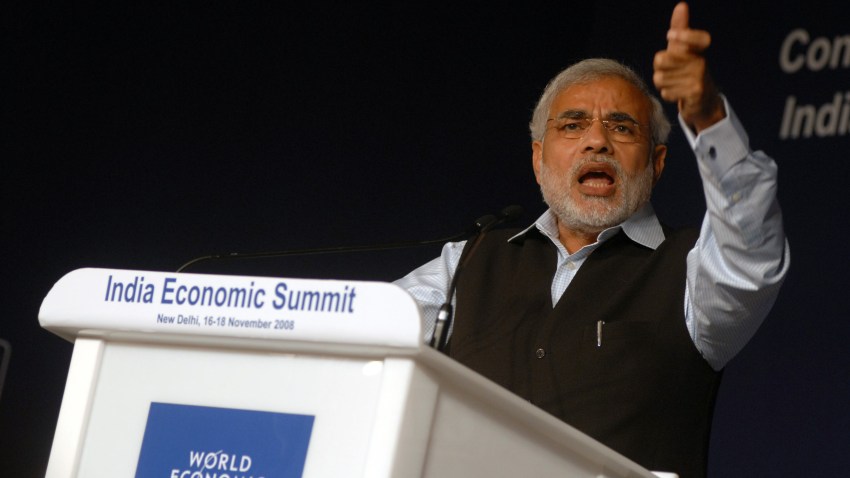

When election results are announced on May 16, they will most likely show Narendra Modi becoming India’s next prime minister. Modi has a troubling track record, as does his party, the nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, better known as the BJP.

Fighting against this outcome is the young scion of a family whose name is legend, Rahul Gandhi. He would be the fourth generation in his family to become prime minister, following in the footsteps of his great-grandfather, Jawaharlal Nehru, who was the country’s founding prime minister; Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi; and her son, Rahul’s late father, Rajiv Gandhi.

The two leading candidates could not be more different. Gandhi is Indian royalty, born, bred and anointed for power. Modi is a self-made man, who rose through hard work, grit and a visceral appeal to the people.

The prospect of a victory by the charismatic Modi, a former tea-seller who became chief minister of the state of Gujarat, fills India’s Muslims and many international observers with a sense of dread. Modi has governed Gujarat with dynamism, presiding over strong economic growth. But he also played a role in sectarian violence in the past. Modi was the man at the helm of Gujarat in 2002 when ethnic riots broke out and a mob of Hindus massacred almost 2,000 Muslims. He has softened his rhetoric since then, but he still strikes many as unrepentant.

If Modi wins, the international community will have to swallow hard and accept the Indian electorate’s decision. The U.S., for example,

revoked his visa years ago. But that decision will likely be reversed, even if, as prominent publications have declared, Modi is still associated with divisive, dangerous, even deadly sectarian politics.

Indian voters will make their choice in an election so massive that it

takes five weeks to complete. With more than 800 million voters, this is not just the world’s largest election. It is most likely the biggest election in the history of the world. Ponder this fact for a moment: India has 300 million more voters that the next three largest democracies combined.

The technical aspects of the ballot are fascinating. With so many voters to reach, campaigns have resorted to a host of creative strategies,

including 3D virtual political rallies. Not surprisingly, technology is playing an enormous role, with social media transforming the ability of politicians to reach potential supporters.

According to polls, Modi and his BJP are all but assured victory. If the polls are correct, the BJP and its closest allies could capture an outright majority of seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Parliament. That would bring the political right to power in India for the first time in a decade, pushing out the Congress party, whose rule has been marred by endless corruption scandals and flagging economic growth.

The polls look convincing, but there is no guarantee that they are fully reliable. And Gandhi is trying to instill a sense of change in the possibility of his rise to the top job, vowing to battle corruption vigorously while empowering women and rekindling economic growth.

In fact, the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance lost power in 2004

despite polls widely predicting victory. That was when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance regained a legislative majority and the prime minister’s post.

After a decade in power, Congress faces an angry electorate. GDP growth has plummeted from more than 10 percent in 2010 to just 4.5 percent in 2013. The race for economic growth that once pitted India versus China has a clear winner,

and it is not India.

The disappointment has extended to high-profile corruption cases, which have added to the feeling that the country is not in good hands, a sentiment that has helped propel Modi’s candidacy.

Gandhi is hoping that by mobilizing young Indians and women, and capitalizing on the power of his name, he will be able to overcome the damage of the recent scandals. He has one more demographic advantage: India’s Muslims, who make up 15 percent of the electorate, rightly view the BJP with deep suspicion.

Both Congress and the BJP vow to stick with the free market and create millions of jobs, further confirmation that India’s “nonaligned” economic policies are dead and buried. And both parties vow to fight corruption and improve working conditions. There are hints, though, that foreign investment could face some restrictions under BJP rule.

When it comes to security, all the main parties promise to fight terrorism and defend the country against its enemies. The BJP, however, strikes a strident nationalist tone, and offers some disturbing security proposals.

In the party’s manifesto the BJP says it will alter India’s nuclear doctrine, under which the country currently has an explicit “no first use” policy. While the Congress manifesto speaks only of nuclear energy, the BJP’s manifesto includes a full section on nuclear strategy, pledging to “revise and update” nuclear doctrine and “make it relevant to challenges of current times.”

For most Indian voters, the bottom line is quality of life. The issue of personal safety ranks at the top of women’s concerns. And everyone

worries about cost of living, economic growth and government services.

The challenge for Gandhi is to make himself look like the candidate of the future, of change, and to build a demographic combination for success. But 10 years after Gandhi’s Congress took the reins, the odds favor the opposition. In this historic election, that means it is Modi, despite his baggage and the fear he instills, who is likely to assume power.

Frida Ghitis is an independent commentator on world affairs and a World Politics Review contributing editor. Her weekly WPR column, World Citizen, appears every Thursday.

Photo: Narendra Modi, Chief Minister of Gujarat, India, New Delhi, India, Nov. 16 2008 (World Economic Forum photo).