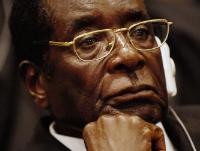

Pray for Zimbabweans. Their economy, shrinking for a decade, is suffering hyperinflation of more than 230 million percent. The government, which has no money to keep most primary and secondary schools open, has even closed down several hospitals during a cholera epidemic. The disease has left nearly 1,200 people dead and more than 23,000 others infected, according to the United Nations. With food, water, electricity and public services all scarce, Zimbabwe confirms Hobbes' belief in the harshness of existence. President Robert Mugabe, the country's sole leader since independence in 1980, deserves much of the blame. He has clung to power, emboldened by his ZANU-PF party, no matter what the national cost. Still, it is unclear how to effect the necessary change to begin Zimbabwe's reconstruction. For Western officials, that process no longer includes a role for Mugabe, with outgoing U.S. President George W. Bush going so far as to say recently, "It is time for Robert Mugabe to go." The stalemated Sept. 11 power sharing agreement, which attempted to create an inclusive government between ZANU-PF and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai's Movement for Democratic Change, is now a non-starter for the U.S. and perhaps Britain. Beyond their rhetoric, the U.S. and the European Union have also imposed sanctions on members of Mugabe's regime and his financial enablers.

Getting to a Post-Mugabe Zimbabwe