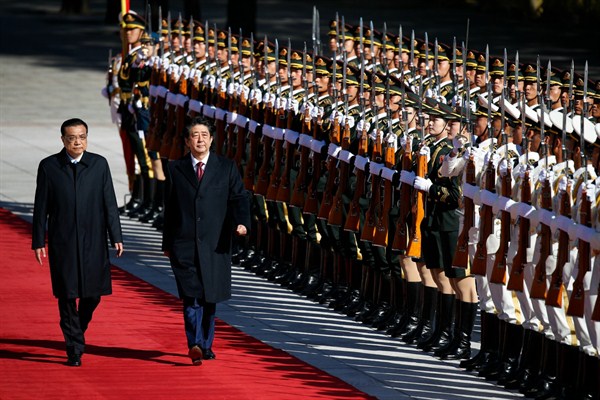

The atmosphere during Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s rare visit to China last week, the first by a Japanese leader since 2011, was loaded with historical meaning. Oct. 23, two days before Abe arrived in Beijing, was the 40th anniversary of the two countries’ Treaty of Peace and Friendship coming into effect. That agreement formally ended their state of war.

The anniversary has now become a convenient touchstone for two countries seeking to normalize relations following a multi-year chill, mainly over disputed islands in the East China Sea and sensitive historical issues. And in the 1970s, as in 2018, it was U.S. foreign policy—intentionally or not—that helped to bring Asia’s two largest economies closer together.

As Japan rebuilt its industrial and manufacturing base following the destruction of World War II, it needed overseas markets for its exports, and mainland China provided a prime opportunity. But Japan was restrained from engaging economically with China by its ally, the United States, which was laser-focused on containing communism. It was none other than Abe’s maternal grandfather, then-Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, who visited the White House in 1957 and told President Dwight Eisenhower that Japan’s limited size and large population meant it “must depend on foreign trade” for economic growth, and that it already had “geographical and historical relationships with China,” according to a U.S. government memorandum at the time. But Eisenhower discouraged Kishi from expanding trade with China, as did successive American administrations.