Since the 1998 election of former President Hugo Chavez, the Venezuelan government has sought to bolster its state sovereignty and reduce its dependence on the U.S. These efforts have involved, among other strategies, strengthening relations with regional allies

such as Cuba and Bolivia,

shoring up new regional institutions such as the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and cracking down on domestic nongovernmental organizations that rely upon U.S. funding for survival.

As a petro-state, however, Venezuela remains heavily reliant upon its oil industry for revenues. If Venezuela is to ever truly reduce dependence on the U.S., it must diversify its trading clientele. While it

has enhanced relations with a number of countries outside of Latin America, including Belarus, Iran and Russia, China has emerged as the most prominent contemporary actor in Venezuela. And after Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recent visit to Venezuela, China is now poised to replace the U.S. as Venezuela’s largest oil consumer.

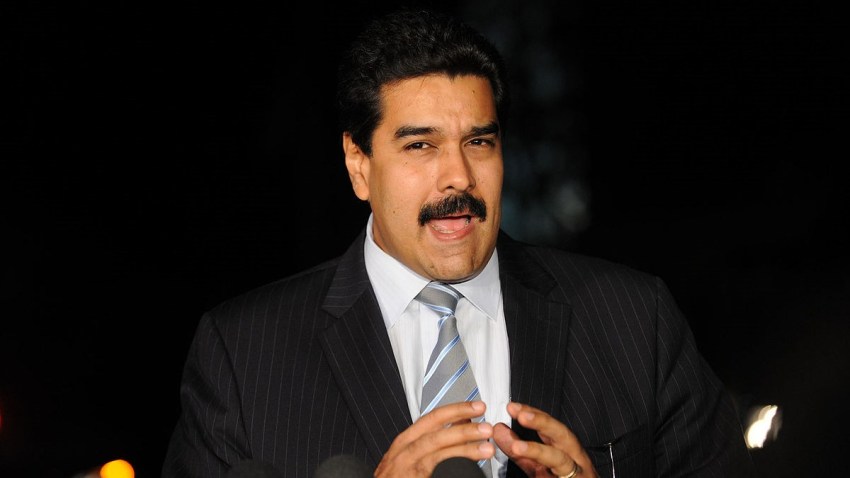

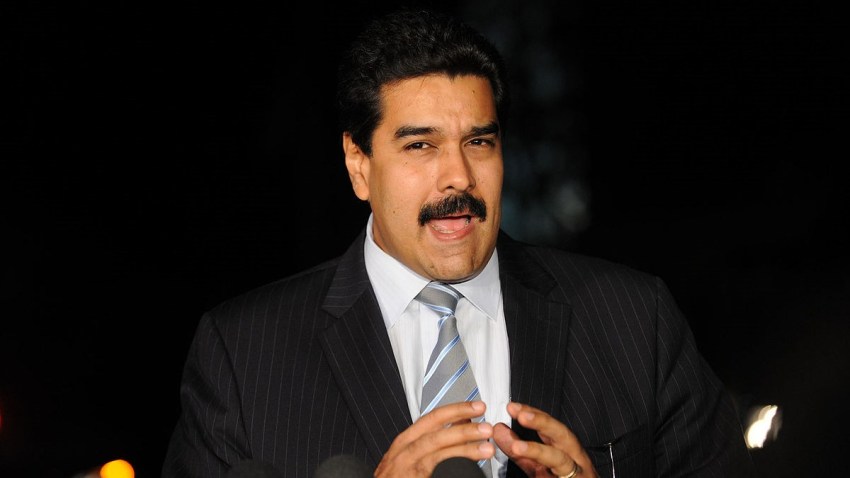

Wang concluded his visit on April 21 after having met with Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and Foreign Minister Elias Jaua. Wang

affirmed that China “hopes that relations between China and Venezuela will continually develop, producing benefits for both countries.” Wang also

expressed support for the national dialogue underway between the government and opposition,

following protests that developed in February.

For Venezuela’s part, Maduro asserted that the Venezuelan government

plans to soon send a million barrels of oil per day (bpd) to China. If that happens, China will replace the U.S. as Venezuela’s largest consumer of oil. And while it may be true that the Chinese government delights in balancing U.S. political power by supporting governments that express anti-U.S. sentiments, the Chinese government remains most clearly interested in securing preferential access to Venezuelan oil, especially the oil reserves located in the Orinoco River Basin. In fact, Chinese diplomats

reportedly openly acknowledge that their government’s unprofitable development and infrastructure ventures in Venezuela are merely a means to securing access to Venezuelan oil.

For the Chinese government, however, the continued political and economic stability of Venezuela’s socialist government amid the recent protests remains critical for the health of Chinese investments and prospective preferential oil access. Many Venezuelan opposition leaders

have criticized the current government’s oil-for-loans deals and have insinuated that they would end these agreements if elected.

The Venezuelan opposition, if it gained power in the near future, would not be able to ignore China and its thirst for oil. But such a development would complicate China’s position in the country. Since 2007, the Chinese government

has provided Venezuela with over $50 billion in loans, which the Venezuelan government repays with shipments of oil. It is through these loans that the Venezuelan government has managed to sustain many of the social aims of Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution. The Venezuelan government has used them to finance several high-speed rail lines in the capital region, housing projects throughout the country and the development of its gold mining industry, among other ventures. And while these projects might not be profitable, many of these loans involve contracts for Chinese services and products, including agricultural technology, aircraft, construction firms and steel, that would most likely evaporate if the opposition were to gain power.

Chinese demand has also allowed the Venezuelan government to reduce its relative dependence on the U.S. And while some observers believe the Venezuelan government merely uses the U.S. as a ruse to distract public opinion from domestic problems, this cannot explain why Caracas would be so adamant about reducing trade with the U.S., whose purchases have also historically allowed the Venezuelan government to finance its Bolivarian Revolution. Since May 2003, the level of Venezuela’s oil shipments to the U.S.

has consistently diminished from 1.73 million bpd to a low of 542,000 bpd in February 2013. The Venezuelan government

has also nationalized both large and small U.S.-owned corporations in many sectors.

Still, it would be shortsighted to suggest that the Venezuelan government has completely eliminated its dependence upon the U.S., which remains Venezuela’s largest trading partner. In 2012, Venezuela

sent nearly 40 percent of its exports to the U.S. and received over 30 percent of its imports from the U.S.

What has more clearly diminished over the past few years, however, is U.S. political influence in Venezuela. Washington and Caracas have not exchanged ambassadors since 2010, and, within the past year, the Venezuelan government

has expelled a number of U.S. diplomats for alleged efforts to destabilize the country. Venezuela has also reduced its involvement in the Inter-American human rights system by

exiting the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In its place, Caracas has become much more involved with groups that exclude the U.S., including CELAC and UNASUR.

For now, Beijing can be assured that the Maduro government will not be immediately ousted from office and that China will continue to receive access to Venezuelan oil. However, it is clear that Venezuelans across the political spectrum have serious economic grievances. In the medium term, public opinion

may not bode well for the Maduro government, and this could have serious repercussions for the Chinese government. While the U.S. continues to maintain economic clout in Venezuela and can be expected to for some time, U.S. government relations with Venezuela are tenuous. Although still significant, the Venezuelan government has reduced its relative dependence on the U.S. oil market, but at the cost of committing its natural resource wealth to China. A fragile equilibrium exists, but political winds may shake the balance if the Maduro government cannot solve its economic problems.

Timothy M. Gill is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia. His research focuses on U.S. democracy assistance and international funding for nongovernmental organizations in Venezuela. He is also a regular contributor to the Washington Office on Latin America’s Venezuelan Politics and Human Rights blog.