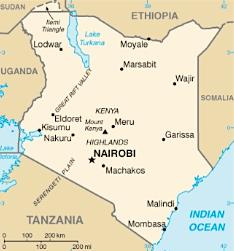

NAIROBI, Kenya -- "We hurriedly buried the seven in the shallow grave and fled due to fears of attacks," explained cattle farmer Joseph Mwangi-Macharia last month as armed police accompanying him went through the motions of unearthing the bodies of his entire family, unwitting victims of the violence that followed Kenya's disputed December 2007 election. "This was my lovely wife. They decapitated her when she pleaded that they spare her 18-year-old granddaughter," said the 52-year old Mwangi-Macharia amid sobs, "Why in God's name did they have to kill her in this fashion?" As the seven bodies were interred in Kenya's Rift Valley province, a flashpoint of some of the deadliest intertribal skirmishes, a moral dilemma was also confronting Kenya's people and leaders: Would a blanket amnesty for perpetrators of crimes against humanity -- such as those who wiped out Macharia's entire family -- be a pragmatic way for the country to get past recent events? Or would it constitute an injustice of epic proportions, given the circumstances that led to the formation of the now two-month-old coalition government?

Kenya Debates Amnesty for Perpetrators of Post-Election Violence