After an uptick in violence in June threatened peace talks between Colombia and the country’s largestguerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, progress since July, when the FARC reinstated its cease-fire, led both sides to declare recently that a final deal was close at hand. But even if an agreement is reached, challenges to establishing a sustainable peace will persist, both for Colombia and its international partners.

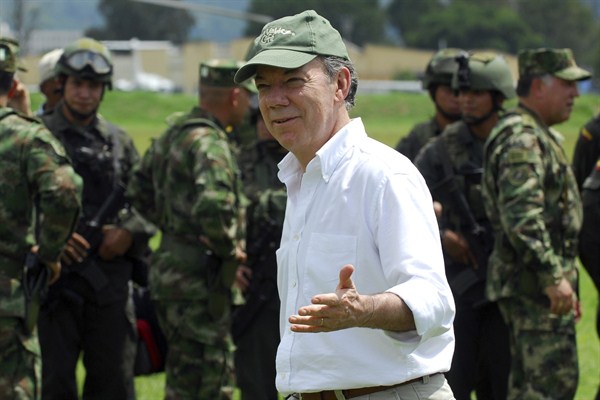

Since negotiations began in October 2012, the peace talks have divided Colombians, with periods of optimism interspersed with moments of dismay. Despite winning re-election in 2014 based on his approach to ending the conflict with the FARC, President Juan Manuel Santos has been forced to maintain a delicate balancing act among the various stakeholders to overcome the numerous obstacles to peace on both sides of the conflict.

Santos’ Re-election No Guarantee for Colombia Peace

After Santos’ June 2014 re-election, Eric Farnsworth wrote that the vote was a referendum on his government’s peace negotiations with the FARC. But while observers began to look ahead toward implementing the peace accords, Farnsworth cautioned that Santos, going into his second term, must be even more conscious of the need to maintain the Colombian people’s support for the negotiations, which may in turn require a stiffened posture toward the FARC.

At the outset of the talks, Colombian civil society was for the first time invited to contribute to peace negotiations between the government and FARC rebels, with the discussion focused on a root cause of the country’s war: land reform. In January 2013, Carolina Ramirez wrote that activists, while optimistic, were skeptical over whether Santos would implement necessary measures for land restitution.

After nine months of deliberations in Havana, Cuba, negotiators were making slow but steady progress in ending the conflict between the government and the FARC. But, wrote Adam Isacson in July 2013, if Colombia does not also reach a peace deal with the National Liberation Army, a smaller, lesser-known leftist insurgency known by its Spanish acronym ELN, successful negotiations with the FARC will be undercut.

Although in March 2015, Colombian negotiators seemed to be inching toward a peace agreement with the FARC, Michael Shifter wrote that Santos’ main concern would be his immediate predecessor, former President Alvaro Uribe, who has been relentless in his opposition to an eventual accord.

Amid a spike in FARC attacks and a damning report on human rights abuses by the army, Santos reshuffled the Colombian armed forces, replacing senior leadership in the army, navy and air force in July 2015. Adam Isacson wrote at the time that the move was aimed to keep peace talks afloat by putting in place a general staff more amenable to a deal.

From Paper to Peace:

Although the possibility for reaching an agreement now looks increasingly real, successful negotiations would not translate automatically into a sustainable peace. Even if a deal is reached, Colombia’s leaders and citizens will face challenges to national reconciliation that will require careful and far-reaching reforms.

After It Makes Peace, Colombia Must Govern

Colombians under 65 have never known peace, Adam Isacson wrote in April 2013, as negotiations in Havana made initial progress toward resolving the country’s civil war. Moreover, the challenges of turning an agreement in Havana into peace in Colombia, from establishing effective governance in former FARC-controlled territory to disarming former insurgents, would require an enormous effort by Colombia and a shift in the focus of U.S. support.

Colombia’s conflict has always looked different from the vantage point of its poverty-stricken FARC-controlled regions. In an August 2015 feature article, James Bargent reported from “the other Colombia,” where FARC guerrillas have fought the military for over half a century—and where the peace agreement those rebels are currently negotiating will face its toughest tests.

Despite promising rhetoric from U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, diplomatic relations between Washington and Bogota are “on autopilot,” Isacson wrote in September 2013. In anticipation of potential peace, the U.S. must instead work with Colombia’s police and armed forces on reforms, “enabling them to protect citizens from the wave of regional ‘criminal groups’ likely to emerge” after a deal is reached.

In September 2015, the mayor of Colombia’s main port city, Buenaventura, was arrested on corruption charges. In an October interview with WPR, Elisabeth Ungar Bleier, executive director of Transparency International’s Colombian chapter, argued that rampant corruption, which “permeates all levels of government and society, public and private,” could undermine the FARC peace deal, the success of which will require transparency and accountability.

Following a spike in violence in the summer of 2015, the FARC declared a second unilateral cease-fire in July. The calm that followed re-established confidence in the talks, and in September both sides committed to reaching a final deal by March 2016. Writing in October, Adam Isacson outlined ways that Colombia’s international partners, including the United States, European states and international organizations, could help make the resulting peace sustainable, but cautioned that, for a variety of reasons, these parties have yet to prepare for this vital work.

More World Politics Review