A new court in the Central African Republic has justice advocates hoping the notoriously unstable nation might finally see some accountability for grave human rights violations committed on its soil. Architects of the United Nations-backed Special Criminal Court describe it as a low-cost way of holding trials for atrocity crimes that could also provide a new model for collaboration between domestic and international justice efforts. But the court faces a daunting array of potential challenges, chief among them renewed violence, scarce funds and weak political will—all factors that have doomed accountability initiatives there in the past.

On Feb. 15, Congolese military prosecutor Toussaint Muntazini Mukimapa was named the lead prosecutor of the court, whose staff will include foreigners and Central Africans. Mukimapa, who was chosen in part for his record of prosecuting war crimes and crimes against humanity in Congo, is expected to start work next month.

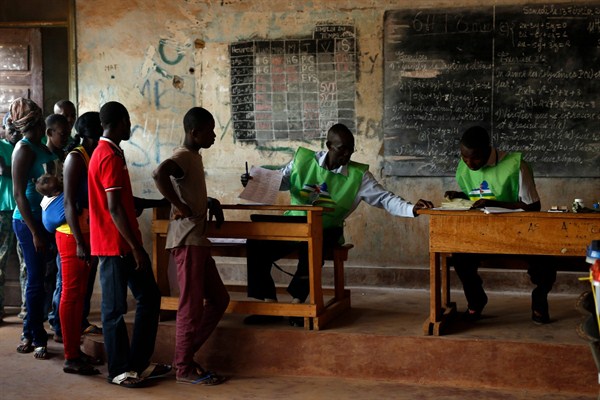

The court was proposed by a transitional government that assumed control of the Central African Republic in 2014. At the time, the country was reeling from a brutal period of violence that began when a mostly Muslim rebel coalition known as the Seleka launched an assault on the government of then-President Francois Bozize, who had been in power since 2003. The rebels toppled Bozize in 2013 and installed their leader, Michel Djotodia, as interim president. But their egregious human rights abuses, including the wanton killing of civilians and destruction of villages, prompted a reprisal campaign by the Christian and animist anti-Balaka militias. Violence soon spread throughout the country, resulting in thousands of deaths and forcing more than 1 million people from their homes, including tens of thousands of Muslims who fled for their lives to Chad, Cameroon and Congo.